THE BOY IN THE BOX

THE TRAGIC STORY OF AN AMERICAN UNSOLVED MYSTERY

The most enduring mystery to ever perplex Philadelphia detectives came to light on the evening of February 23, 1957, when a La Salle College student parked his car off Susquehanna Road and began to hike across a vacant lot in the drizzling rain. The unnamed young man – various newspaper reports put his age between 18 and 26 – was a “Peeping Tom” and was en route to spy on the inmates of the nearby Good Shepherd Home, a Catholic residence for “wayward” girls. But what he found as he walked across the overgrown lot that night would destroy any interest that he had in looking in young girl’s windows.

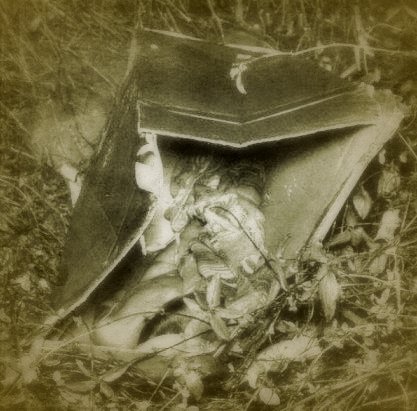

It was a cardboard box, seemingly innocuous – until he looked inside and saw that a small corpse had been wedged into it. Terrified, he forgot about the undressed women that he had come to see. He turned and ran back to his car. Frightened and embarrassed, the man confessed his discovery to his priest the next day and he was told to call the police. He complied, after first concocting a tale that he found the box while chasing a rabbit through the weeds, and officers were sent to the lot to investigate.

This would be the beginning of a heartbreaking story to which the end has yet to be written.

The patrolmen who arrived at the vacant lot on February 24 found a large cardboard carton lying on its side, open at one end. The box had once held a baby bassinet from J.C. Penney. Inside the box was a small boy, his pale white body wrapped in a cheap, imitation Indian blanket. They searched the lot and 17 feet from the box, discovered a man’s cap, made from royal blue corduroy with a leather strap and a buckle on the back. Coincidentally or otherwise, a beaten path through the weeds and the underbrush led directly from the cap to the cardboard coffin.

An autopsy was performed on the boy by Dr. Joseph Spelman, Philadelphia’s chief medical examiner. His report placed the boy between four and six years old. He had blue eyes and light blond hair that had been badly cut, closely shorn in some areas of his head, shaved almost to the skull in others. He was 41 inches tall and weighed only a pathetic 30 pounds at the time of his death. Dr. Spelman cited the cause of death was a savage beating that left the boy’s body and face covered in fresh bruises. Older marks included an L-shaped scar on his chin; a one-inch surgical scar on the left side of his chest; a round, irregular scar on his left elbow; a well-healed scar at the groin, apparently from hernia surgery, and a scar on the left ankle that resembled a “cut down” incision used to expose veins for a blood transfusion. The boy was circumcised but had no vaccination marks, suggesting that he had not been enrolled in public school.

Spelman’s report contained many other intriguing details. The victim’s right palm and the soles of both feet were rough and wrinkled, which suggested that they had been submerged in water, immediately before or after death. When exposed to ultraviolet light, the boy’s left eye fluoresced a bright shade of blue, indicating recent exposure to a diagnostic dye used in the treatment of chronic eye disease. Spelman attributed the boy’s death to head trauma, probably inflicted with a blunt instrument, but he could not rule out that damage had been done by “pressure” – which prompted some of the investigators to suggest that fatal damage had been inflicted by someone squeezing the boy’s head when he was given his last, botched haircut. Detectives clothed the boy and photographed his battered face, in hopes that they might be able to learn his name – but those hopes slowly died with the passing years.

Investigators initially focused on the box that had been used as the boy’s coffin. It had originally held a baby bassinet from J.C. Penney and was one of a dozen received on November 27, 1956 and sold for $7.50 between December 3, 1956 and February 16, 1957 from a store in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. The store, though, kept no record of individual sales, but the other 11 bassinets were eventually located by detectives. FBI fingerprint technicians found no usable prints on the carton recovered from the empty lot.

The examination of the blanket proved to be just as frustrating. It was made from cheap cotton flannel and had been recently washed and mended using poor-grade cotton thread. It had been cut into two separate, unequal pieces and then wrapped around the naked boy. Analysis at the Philadelphia Textile Institute determined that it had been manufactured either at Swannanoa, North Carolina, or Granby, Quebec. Identical blankets had been produced by the thousands, and the police were never able to figure out a likely place where it had been sold.

A label inside of the blue cap led police to Robbins Eagle Hat & Cap Company in Philadelphia. Proprietor Hannah Robbins said that it was one of 12 that had been made from corduroy remnants at some point prior to May 1956. Robbins recalled the particular hat because it had been made without the leather strap, but the purchaser – a blond man in his late twenties – had returned a few months later to have a strap sewn on. Robbins told the detectives that her customer resembled photographs that she was shown of the “Boy in the Box,” but she had no record of his name or address.

Philadelphia police circulated more than 10,000 flyers with the child’s photograph on them to police departments throughout eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey, but with no results. The Philadelphia Gas Works mailed out 200,000 flyers to its customers with their monthly gas bills, while more were circulated by the Philadelphia Electric Company, grocery stores, insurance agents, and a pharmacist’s association – about 300,000 flyers in all. An article about the case was written for the FBI’s Law Enforcement Bulletin, again without producing any worthwhile leads. Someone, somewhere, knew who the boy was and what had happened to him, but they were not talking.

Five months after the boy was found, the authorities buried him in Philadelphia’s potter’s field, near the Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry, a mental institution. The beleaguered detectives who worked the case collected enough money to erect the grim graveyard’s only headstone. Its inscription read: “Heavenly Father, Bless this Unknown Boy.”

The case went cold, silent and deathly still until November 4, 1998, when the “Boy in the Box” was exhumed in order to extract DNA samples, collected for future comparison with any suspected relatives. A year passed before the authorities finally admitted that they had not been able to obtain a satisfactory DNA profile from the boy’s remains. Another attempt was made in 2000, this time from the boy’s teeth, but this attempt also failed. A second attempt, though, was reported as successful in April 2001. Although the discovery of any living relatives seems fairly hopeless at this point, some investigators have remained optimistic.

In 1999, Frank Bender, a forensic artist and a founding member of the Vidocq Society, came up with a new idea that he believed might help solve the case. The Vidocq Society is a crime-solving organization that is based out of Philadelphia. The group is named for Eugène François Vidocq, the ground-breaking nineteenth-century French detective who helped police by using criminal psychology to solve "cold case" homicides. At meetings, the members – forensic professionals, current and former FBI profilers, homicide investigators, scientists, psychologists, prosecutors and coroners -- listen to law enforcement officials who come from around the world to present unsolved cases for review. Bender sculpted a bust that he believed could bear a strong resemblance to the dead boy’s father. The case was profiled for a national television audience on America’s Most Wanted, but no leads were discovered. Regardless, efforts to identify the boy continue.

Like most unsolved murders, there have been a number of theories advanced toward a solution of the case. Most of the “Boy in the Box” theories were dismissed, but two possible solutions created interest in recent years.

The first, which was eventually ruled out, involved a foster home that was located a little more than a mile from the vacant lot where the boy’s body was found. In 1960, Remington Bristow, an employee of the medical examiner's office who doggedly pursued the case until his death in 1993, contacted a New Jersey psychic, who told him to look for a house that seemed to match the foster home. When the psychic was brought to the city, she led Bristow straight to the house. Bristow refused to let it go, investigating the case on his own. When he attended an estate sale at the foster home, Bristow discovered a bassinet similar to the one sold at J.C. Penney. He also saw blankets hanging on the clothesline similar to that in which the boy's body had been wrapped. Bristow believed that the child belonged to the stepdaughter of the man who ran the foster home. He believed that the stepfather was involved in a sexual relationship with the girl and she became pregnant. The boy was hidden away, but when he died accidentally, the man disposed of the boy so that the girl would not be exposed as an unwed mother, a significant social stigma in 1957.

Despite this circumstantial evidence, the police were unable to find any real links between the family and the Boy in the Box. In 1998, Philadelphia police lieutenant Tom Augustine, who remains in charge of the investigation, and several members of the Vidocq Society, interviewed the stepfather and the daughter, whom he had married. The interview seemed to confirm to them that the family was not involved in the case. After a DNA test, which ruled out the stepdaughter as the boy’s mother, the investigation of the foster home theory was closed.

The second theory emerged in February 2002, reported by a woman identified only as "M." She claimed that her abusive mother purchased the unknown boy, named "Jonathan," from his birth parents in the summer of 1954. The youngster was subjected to extreme physical and sexual abuse for two and a half years. Her mother then allegedly killed the boy in a fit of rage when he vomited in the bathtub. The woman then cut the boy’s long hair (accounting for the ragged haircut) and dumped the body in the secluded vacant lot. "M" went on to say that as they were preparing to remove the boy's body from the trunk, a passing male motorist pulled alongside to inquire whether they needed assistance. They ignored him and he eventually drove away. This story corroborated confidential testimony given by a male witness in 1957. The police considered the story quite plausible, but were troubled by "M"'s testimony, because she had a history of mental illness. When interviewed, though, neighbors who had access to the house denied that there had been a young boy living there, and said that "M"'s claims were "ridiculous."

And so the case remains unsolved. Despite the huge amount of publicity at the time and sporadic re-interest throughout the years, the case remains unsolved to this day, and the boy's identity is still unknown.