NOT FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET...

THE HAUNTING, UNSOLVED MYSTERY OF "SUPERMAN" GEORGE REEVES

Superman died at 1:59 am on June 16, 1959. Not the comic book character, of course, but the man who personified the "real" Superman for an entire generation of television fans. George Reeves, it was discovered, was not faster than a speeding bullet after all. Even though the initial coroner’s report listed Reeves’ death as an "indicated suicide," after nearly five decades there are many who do not believe that he killed himself. The death of George Reeves remains one of Hollywood’s most compelling unsolved mysteries, combining rumors of murder, conspiracy, cover-ups – and a lingering ghost.

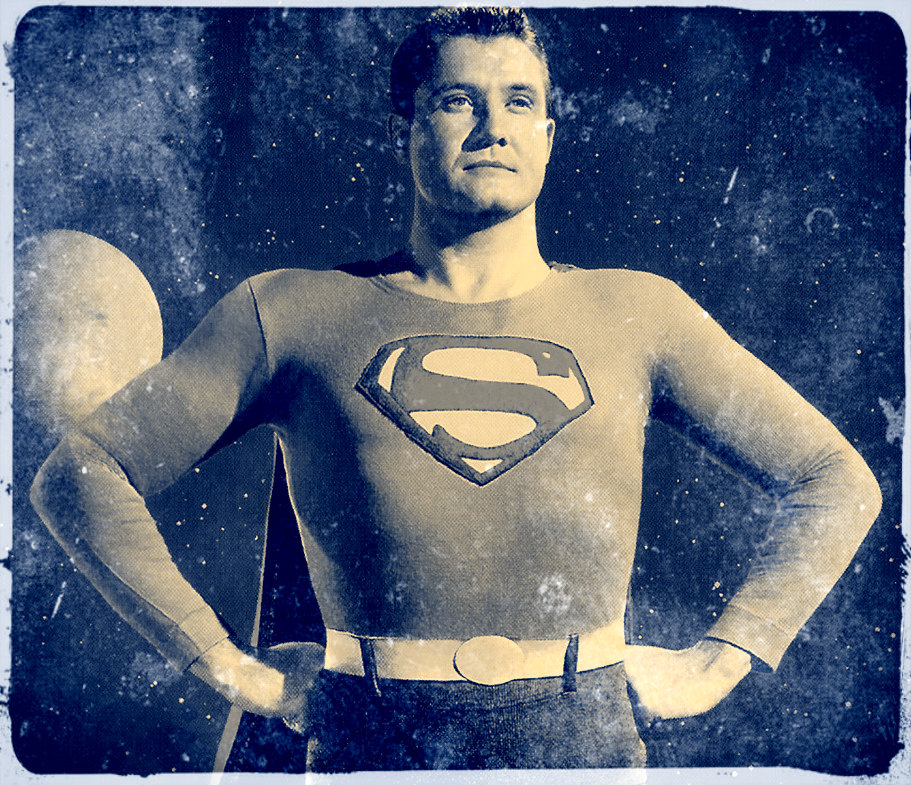

George Reeves

He was born George Keefer Brewer in Woolstock, Iowa, the son of Don Brewer and Helen Lescher, just five months into his parents’ marriage. The pair separated soon afterward, and Helen moved back home to Galesburg, Illinois. A short time later, George’s mother moved to Pasadena, Calif., to stay with her sister and there, she met and married Frank Bessolo. In 1927, Frank adopted George as his son, and the boy took on his new stepfather's last name to become George Bessolo. Helen's marriage to Frank lasted 15 years and ended in divorce while George was away visiting relatives. Helen told George that Frank had committed suicide. It would not be until George joined the Army during World War II that he discovered a number of things that his mother had hidden from him. She had concealed his true birth date and the fact that Bessolo was still alive and that he was actually George’s stepfather, not his biological father. This information disturbed Reeves so much that he did not speak to her through most of the 1940s.

Growing up, George was an accomplished athlete and in 1932, entered the Golden Gloves boxing competition against his mother’s wishes. He did well in the event and went to the Olympics in L.A. in 1932. After having his nose broken nine times, he hung up his gloves and decided to pursue acting. He had started acting and singing in high school and continued performing on stage as a student at Pasadena Junior College. Accepted by the Pasadena Playhouse, Reeves had prominent roles. His film career began in 1939, when he was cast as Stuart Tarleton, one of Vivien Leigh's suitors in “Gone with the Wind.” It was a minor role, but he and Fred Crane, both with brightly dyed red hair as "the Tarleton Twins," were in the film's opening scenes. He was contracted to Warner Brothers at the time, and the actor's professional name became "George Reeves." He married actress Ellanora Needles in 1940, but had no children with her during their nine-year marriage.

Reeves starred in a number of two-reel short subjects and appeared in several low budget pictures, including two with Ronald Reagan and three with James Cagney. Warner Brothers loaned him out to co-star with Merle Oberon in “Lydia,” a box-office failure. After his Warner Brothers contract expired, he signed on with Twentieth Century-Fox but was released after only a handful of films. He freelanced, appearing in five Hopalong Cassidy westerns before he was cast as Lieutenant John Summers, opposite Claudette Colbert, in “So Proudly We Hail!” The war drama for Paramount won him critical acclaim for the role and considerable publicity.

A publicity shot for the Superman television series

Reeves was drafted into the Army about 18 months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In late 1943, he was transferred to the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) and assigned to the Broadway show “Winged Victory,” produced by and for the USAAF. A long Broadway run followed, as well as a national tour and a movie version of the play. He was later transferred to the USAAF’s First Motion Picture Unit, where he made training films.

After the war ended, Reeves returned to Hollywood but many studios had slowed down their production schedules and others had shut down completely. He took work where he could find it, including in some outdoor thrillers with Ralph Byrd and a serial called “The Adventures of Sir Galahad.” These were low-budget films for which Reeves simply fit the rugged casting requirements and, with his retentive memory for dialogue, could do well under rushed production conditions. He also played against type with one villainous role as a gold hunter in a Johnny Weissmuller “Jungle Jim” film, which turned out to be a moderate success for a B-picture.

In the autumn of 1949, Reeves (whose divorce had recently become final) decided to move to New York. While there, he performed on several live television anthology programs, as well as on radio. Reeves returned to Hollywood in April 1951, specifically for a role in a Fritz Lang film, “Rancho Notorious.”

In June 1951, Reeves career permanently changed when he was offered the role of Superman in a television series. He was initially reluctant to take the role because, like many actors of his time, he considered television to be unimportant and believed that few would see his work. He worked for low pay, even as the star, and was only paid during the weeks of production. The half-hour films were shot on tight schedules of at least two shows every six days.

His career as Superman began with “Superman and the Mole Men,” a film that was designed to be a theatrical picture and the pilot for the television series. Immediately after it was completed, Reeves and the crew began production of the first season's episodes, shot over 13 weeks during the summer of 1951. The series began airing in 1952 and Reeves was astonished when he became a national celebrity in his role as newspaper reporter Clark Kent, who was really Superman. In 1957, the struggling ABC Network picked up the show for national broadcast, which gave him and the rest of the cast even greater visibility. His portrayal of the character became wildly popular and everywhere he went, children and adults alike clamored to meet him and obtain his autograph.

Reeves never resented doing personal appearances as Superman, especially since they paid money beyond his meager salary, and his affection for young fans was genuine. Reeves took his role model status seriously, avoiding cigarettes where children could see him, eventually quitting smoking altogether, and keeping his private life very discreet. But Reeves loved women and many who were close to him stated that he broke the hearts of many of the actresses that he worked with. In 1951, he had begun a romantic relationship with a married ex-showgirl, Toni Mannix, wife of MGM general manager Eddie Mannix. Some believe this affair may have cost Reeves his life.

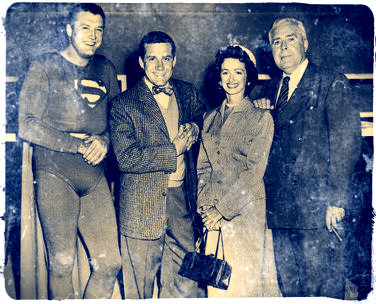

The cast of Superman in a happy moment.

Whether or not Reeves resented being typecast as Superman, he played the heroic role to the hilt, and sometimes not just on screen. With Toni Mannix, Reeves worked tirelessly to raise money to fight myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue. He served as national chairman for the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation in 1955. During the second season, Reeves appeared in a short film for the US Treasury Department, in which he caught some crooks and told kids why they should invest in government savings stamps.

Jack Larson, who played Jimmy Olsen in the series, recalled that Reeves was always a gentleman to the other actors in the show, although he loved to play practical jokes on the cast and crew. He insisted that the original Lois Lane, Phyllis Coates, be given equal billing in the credits in the first season. When Coates was replaced by Noel Neill, Reeves quietly defended her nervousness on her first day when he felt that the director was being too harsh with her. He also stood by Robert Shayne (who played Police Inspector William "Bill" Henderson) when Shayne was subpoenaed by FBI agents on the set of Superman. Shayne's political activism in the Screen Actors Guild in the 1940s was used by his bitter ex-wife as an excuse to lie and say that he was a member of the Communist Party. On the other hand, Reeves delighted in standing outside camera range, making faces at the other cast members to see whether he could break them up. By all accounts, there was a strong camaraderie among the principal actors.

After two seasons, though, Reeves began to get tired of both the Superman role and the low salary he was receiving. He was now 40 and he wanted to move on with his career. He established his own production company and conceived a television adventure series called “Port of Entry,” which would be filmed on location in Hawaii and Mexico. He wrote the pilot script himself and prepared to start pre-production work when the producers of “Superman” offered him a large salary increase. Not wanting to turn it down, he returned to the role.

In 1957, there was talk of producing a new theatrical Superman film and possibly discontinuing the series, but this never happened. Instead, another season of the show was developed. By mid-1959, contracts were signed, costumes re-fitted, and new scripts were assigned to the writers. Noel Neill was quoted as saying that the cast was ready to do a new season of the still-popular show. Producers reportedly promised Reeves that the new programs would be as serious and action-packed as the first season, guaranteed him creative input, and slated him to direct several of the new shows, as he had the final three episodes of the 1957 season.

In between the first and second seasons of “Superman,” Reeves got sporadic acting assignments on television and in two feature films, “Forever Female” and “The Blue Gardenia.” But by the time the series was airing nationwide, Reeves found himself so associated with Superman and Clark Kent that it was difficult for him to find other roles. He also sang on the “Tony Bennett Show” in August 1956 and appeared in an episode of “I Love Lucy” as Superman. His good friend Bill Walsh, a producer at Disney Studios, gave Reeves a prominent role in “Westward Ho the Wagons,” in which Reeves wore a beard and mustache. It was to be his final feature film appearance.

In spite of his sporadic film and television work, and Superman appearances, Reeves was not doing well financially. In 1958, he broke off his affair with Toni Mannix and announced his engagement to society girl, Leonore Lemmon. He complained to friends, columnists, and his mother of his financial problems. The royalties that he was receiving from the syndication of “Superman” were insubstantial, especially in view of his lifestyle. Apparently, the planned new season of the show, as well as his appearances were a much-needed lifeline. Reeves needed money and the only option that he had to make any was by portraying Superman, which he reluctantly agreed to do.

Just three days after his death, he was to have returned to the boxing ring with light heavyweight champion Archie Moore. The exhibition match was to be played on television so that viewers across the country could tune in to see Superman beat the champ. Reeves told reporters, “the Archie Moore fight will be the highlight of my life.”

After the fight, he and Leonore were to be married. They planned to honeymoon in Spain and then go to Australia for six weeks, where Reeves would pick up over $20,000 for appearances as Superman. The series had just been sold to an Australian television network and local viewers were clamoring to meet the “Man of Steel.”

Reeves would then return to Hollywood later in the year to star in a feature film that he was putting together, which he would also direct. He was then scheduled to shoot new episodes of “Superman” and receive another hefty salary increase. Things seemed to being going well for Reeves, even while being stuck playing Superman, and some said that he seemed to have everything to live for.

In the three months before his death, Reeves was involved in three mysterious automobile mishaps. He refused to believe that anyone had tampered with his car, even though a mechanic believed that someone had drained his brake lines.

But all was not perfect in his life. In the three months before his death, Reeves was involved in three mysterious automobile mishaps that almost cost him his life. The first time, his car was nearly crushed by two trucks on the freeway. Another time, a speeding car nearly killed him, but he survived thanks to his quick, athletic reflexes. The third time, Reeves’ brakes failed on a narrow, twisting road. All of the brake fluid, it was discovered, was gone from the hydraulic system, in spite of the fact that an examination by a mechanic found the system was in perfect working order.

"When the mechanic suggested that someone had pumped out the fluid, George dismissed the notion," said Arthur Weissman, Reeves’ best friend and business manager. Weissman always remained convinced that his friend had been murdered. He tried to convince Reeves that he needed to be careful, but Reeves brushed off the warnings.

About a month later, he began to receive death threats on his unlisted telephone line. Most of them came late at night and there were sometimes 20 or more each day. Often, the anonymous caller would simply hang up when Reeves answered. They said nothing, but after a few graphic and detailed threats, Reeves knew it was the same person. Nervous after the near misses in his car, Reeves filed a report with the Beverly Hills Police Department and a complaint with the L.A. District Attorney’s Office. He even went so far as to suggest a suspect, his former lover, Toni Mannix.

It was never explained why Reeves openly pointed the finger at Toni Mannix. Their relationship had never been a public one but it was a badly kept secret in Hollywood. Eddie Mannix was likely aware of the situation and didn’t like it. According to Reeves’ friend Arthur Weissman, Mannix was a disliked, but feared, member of the Hollywood movie industry. Weissman believed that the executive was responsible not only for the threats that Reeves received, but also for the attempts on his life.

The D.A.’s office investigated the complaint filed by Reeves, including his accusations of Toni Mannix’s involvement, but soon discovered that both Reeves and Toni were receiving telephone threats and crank calls. When that was disclosed, many people assumed that it was Eddie Mannix who had instigated the calls through employees or hired thugs.

Weissman believed that Mannix was behind Reeve’s near-fatal auto crashes, as well. In the film and theater business, Mannix had access to a lot of people outside of the general public. For a price, these men could maneuver two trucks close together on the highway, or could drain the brake fluid from someone’s car. Furthermore, he was sure that Mannix also had access to someone who could arrange a murder, too.

George Reeves’ home in Benedict Canyon

On June 16, 1959, Lenore Lemmon served dinner at around 6:30 p.m. at Reeves’ Benedict Canyon home. She had prepared the meal for Reeves and guest Robert Condon, a writer who was there to do an article on Reeves and his upcoming bout with Archie Moore. After dinner, they settled down in the living room to watch television. Around midnight, everyone went to bed. Around 1 a.m., a friend named Carol Von Ronkel came by the house with another friend, William Bliss. Even though the house was the frequent scene of parties and entertaining, Reeves did not want guests after midnight. However, Von Ronkel and Bliss banged on the door until Leonore got up and let them in. George also came downstairs in his bathrobe and yelled at them for showing up so late. After blowing off steam, he stayed with the guests for a while, had a drink, and then retired upstairs again. When he left, Leonore turned to the others who were present and said something along the lines of, “Well, he’s sulking, he’ll probably go up to his room and shoot himself.”

The houseguests later heard a single gunshot. Bliss ran into the master bedroom and found George Reeves dead, lying across his bed, naked and face-up, his feet on the floor. This position has been attributed to Reeves sitting on the edge of the bed when he shot himself, after which his body fell back on the bed and the 9mm Luger pistol fell between his feet.

Superman was dead.

The Beverly Hills police report of the incident states that, while entertaining his fiancée and three others in his home, Reeves suddenly, without any explanation, left the room and impulsively committed suicide. The statements made to the police and the press by those at the house that night essentially agree. Quite some time passed before the police were summoned to the scene, although neither Leonore nor the other witnesses made any explanation for the delay. They claimed that the shock of the death, the lateness of the house, and their intoxication caused the delay – they had nothing to hide. Detectives did say that all of the witnesses were extremely inebriated, and that their coherent stories were very difficult to obtain.

In the press, Leonore attributed Reeves's apparent suicide to depression caused by his "failed career" and inability to find more work, which was clearly not the case. The witness statements and examination of the crime scene led to the conclusion that the death was self-inflicted. A more extensive official inquiry concluded that the death was indeed suicide. Reeves's will bequeathed his entire estate to Toni Mannix, much to Lemmon's surprise and devastation.

Many people at the time, and many more in later years, have refused to believe the idea that George Reeves would kill himself. Even though he believed his friend was murdered, Arthur Weissman surprisingly did not dispute the sequence of events offered by Leonore Lemmon and the other witnesses. He said that this was just how it happened, but that Reeves did not intend to kill himself. He explained that Reeves was just playing his favorite morbid game, a practic with a gun that was loaded with a blank. According to Weissman, that was why Leonore said what she did. All of Reeves’ friends knew that when he was drinking, he would sometimes fire a blank at his head in a mock suicide attempt, making certain that his arm was far enough away so that he didn’t get powder burns on his face. Weissman claimed that, unknown to Reeves, the blank was replaced by a real bullet by someone hired by Eddie Mannix.

Reeves’ clandestine former girlfriend, Toni Mannix, was madly in love with him and according to Weissman, their relationship was an open Hollywood secret. It continued for years and then came to an end when George announced that he was marrying Leonore Lemmon. Friends said that Toni was "enraged" over this development and began bombarding Reeves with phone calls, making all sorts of threats. It was believed that both she and her husband, who was openly humiliated by Reeves over the affair, had the perfect opportunity to seek revenge, especially since Toni possessed a key to the Reeves house. The police never looked deeply into Weisman’s claims of the switched bullet, believing instead that Reeves’ death had been self-inflicted.

Among those who were unhappy with the findings of "indicated suicide" were Reeves’ mother, Helen Bessolo. She retained the Nick Harris Detectives of Los Angeles to look into the case. At that time, a man named Milo Speriglio was a novice investigator at the firm and played a small role in the investigation. "Nearly everyone in Hollywood has always been led to believe that George Reeves’ death was a suicide," he said in a later interview. "Not everyone believed it then, nor do they believe it now. I am one of those who does not." And neither did Helen Bessolo. She went to her grave in 1964 convinced that her son was murdered.

The Nick Harris Agency, which had been founded in Los Angeles before the FBI was even in existence, quickly came to believe that Reeves’ death had been a homicide. Even based on the fact that many of the witnesses that night were intoxicated and incoherent, the detectives felt that they could rule out suicide. Unfortunately, though, the Beverly Hills Police investigators chose to ignore their findings. A review of the facts seemed to indicate the agency’s suspicions were well founded. They also ruled out the idea of Reeves’ “suicide game” as his cause of death – they believed that someone else was in the house at the time he died.

For one thing, the absence of powder burns on Reeves’ face showed that he did not hold the gun to his head, as the police report stated. For the weapon to have not left any facial burns, it had to have been at least a foot and a half away from Reeves’ head, which is totally impractical in a suicide attempt. In addition, Reeves was discovered after his death on the bed, lying on his back. The single shell was found under his body. According to experts, self-inflicted gunshot wounds usually propel the victim forward and away from the expended bullet casing.

Speriglio made a careful examination of the police report and noticed that the bullet wound was described as "irregular." So, the agency reconstructed the bullet entry and exit. The slug had exited Reeves’ head and was found lodged in the ceiling. His head, at the moment of death, would have had to have been twisted, making a self-inflicted shot improbable. Speriglio suspected that an intruder had entered Reeves’ room and that the actor had found his gun. A struggle had followed and Reeves was shot. The intruder then escaped from the house unnoticed.

While interesting, this theory does not explain why the gun (normally loaded with blanks) had a bullet in it and how the intruder escaped from the house with other people inside.

Regardless of whether or not he killed himself, it was obvious that Reeves’ death was never properly investigated. Police investigators never even bothered to take fingerprints at the scene and people like Arthur Weissman believed they were pressured to make it an "open and shut" case. George Reeves, according to the official findings, had committed suicide. But did he really?

We will never know for sure. In 1961, Reeves’ body was exhumed and cremated, forever destroying whatever evidence was left behind. The death of George Reeves will always remain another unsolved Hollywood mystery.

THE GHOST OF GEORGE REEVES?

Could this be why ghostly phenomena has been reported at the former Reeves house ever since his death? Many believe that the ghostly appearances by the actor lend credence to the idea that he was murdered. Over the years, occupants of the house have been plagued by not only the sound of a single gunshot that echoes in the darkness, but strange lights, and even the apparition of George Reeves.

After Reeves’ death, real estate agents attempted to sell the house to settle the actor’s estate. Unfortunately, though, they had trouble. Occupants would not stay long because they would report inexplicable noises in the upstairs bedroom where Reeves died. When they would go to investigate the sounds, they would find the room was not as they had left it. Often, the bedding would be torn off, clothing would be strewn about, and some reported the ominous odor of gunpowder in the air. One tenant also noticed that his German Shepherd would stand in the doorway of the room and bark furiously as though he could see something his owners could not. The phenomenon in the house was so widely witnessed that at one point, two L.A. County deputies were assigned to watch the place because neighbors had reported screams, gunshots, and lights going on and off in the empty house during the night.

New occupants moved out quickly, becoming completely unnerved after encountering Reeves’ ghost, decked out in his Superman costume! The first couple that spotted him was not the last to see him either. Many later residents also saw the ghost and one couple became so frightened that they moved out of the house that same night. Later, the ghost was even reported on the front lawn by neighboring residents.

In the 1980s, while the house was being used as a set for a television show, the ghost made another startling appearance. He was seen by several of the actors and crewmembers before abruptly vanishing, furthering the mysterious elements of this strange and complicated case.

What happened to George Reeves? We will never know for sure and his story is doomed to become another of Hollywood’s many unsolved mysteries.